Before the advent of recorded sound and vision, the mechanics of paying actors and musicians was very similar to the way most other working people was recompensed. To put it (far too) simply, if you were paid at all, you were paid for the hours you worked or the product you made.

The nearest thing to 'recorded music' was sheet music, allowing people to play their own interpretation of the piece, usually on a piano. Royalties were paid to the publisher and artist in a similar manner to book publishing.

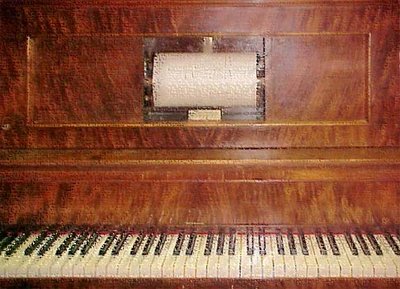

Then came the Pianola, a specially constructed piano which could be controlled via a paper roll which had been 'punched' with a musical piece. These early iPod ancestors could play a piece of music until the paper roll wore out, without any direct interaction from a human being. This presented publishers of music with a dilemma. With printed music, playing the piece was an 'interpretative' act, requiring a human being to perform the piece. These huge rolls of paper were less like a book, and more like a copy of a performance.

In 1908 US Supreme Court ruling that the piano rolls were not illegal copies of a musical performance and legislation was passed recognising recordings and the reproduction of them as being within the rights secured to their authors in copyright law, under a 'mechanical licensing' agreement.

After the piano rolls were succeeded by other forms of recordings the mechanical license royalty system was extended to wax cylinders and eventually to phonographic discs.

------------

No comments:

Post a Comment